CHOCOLATE GEORGE

In 1967, as a general assignment reporter and feature writer for the Los Angeles Times, I made two visits to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, one before and one after the Summer of Love. The first trip produced a series of five pieces about the growing hippie scene, a spell I was starting to fall under. I thought the pieces were pretty good, but I got an angry call from a member of the Los Angeles Diggers, who damned them as straight, superficial and full of shit. They smelled of The Man. I said let’s talk.

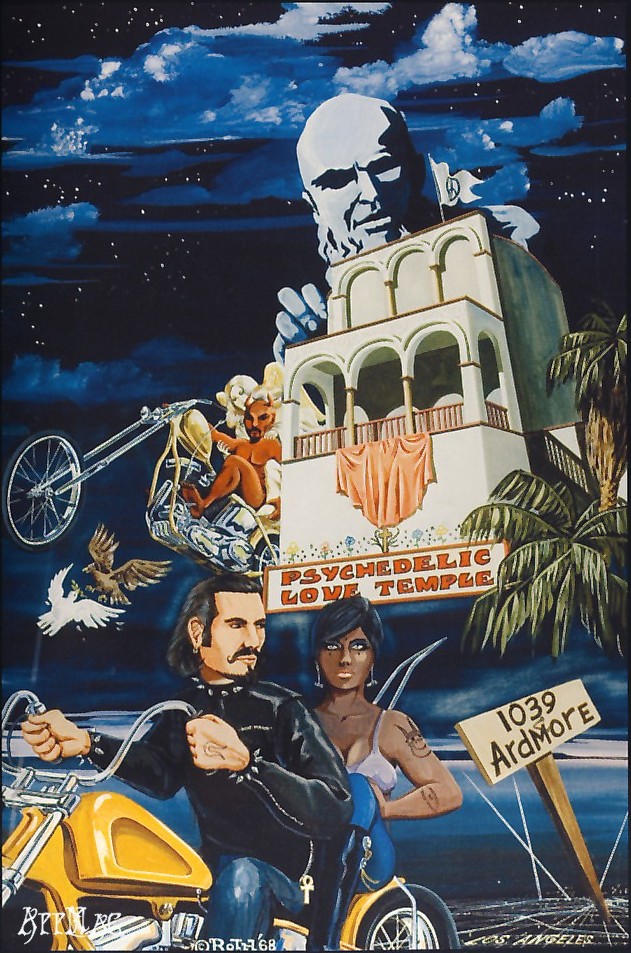

The Diggers and I met by candlelight at midnight in an eerie abandoned mansion known as the San Souci Temple or the Psychedelic Love Temple at 1039 N. Ardmore Ave. The crumbling octagonal building served as a crash pad and party house for local bikers and hippies, and we were surrounded by foam mattresses and peeling psychedelic walls. (A few weeks later Roger Corman shot some scenes there for his film The Trip, written by Jack Nicholson and starring Peter Fonda, Susan Strasberg, Bruce Dern and Dennis Hopper.) Here’s a picture of the place in daylight and a poster of it by Ed Roth and David Mann.

I don’t remember what was said or smoked that night, but the Diggers must have expanded my mind a little. When the Summer of Love was over, City Editor Bill Thomas sent me back to the Haight with the suggestion that I get experimental, “try something new.” He was that kind of editor. He had earlier turned me onto Richard Farina’s book Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. So I decided to use a tape recorder, for the first time. Maybe it was the scolding I got from the Diggers, but I figured a good way for an outsider to cover a new culture was to use mainly their own words.

I taped the words of hippies who still lived in the Haight and those who had moved to other communities in the bay area. Working at home over several weeks, I transcribed and transformed their words into a three act play, Some Observations on the Haight-Ashbury in the Week that Followed the Death of Chocolate George.

I remember handing 30 typed pages to Thomas, and he kind of laughed. “There’s a limit to what we can run, you know.” “That’s Part One,” I said. They eventually ran the whole thing, the longest piece the paper had ever run, and it was certainly different. They didn’t give me a byline because I don’t think they felt the piece was actually written. They gave me credit in an editor’s note and said I had “winnowed” the material from “countless interviews.” Apparently I was a winnower, not a writer. I always thought myself more of a wallower. But I suppose wallowing and winnowing is one approach to journalism.

To their credit the Los Angeles Times did run the whole play, and later reprinted it on heavy paper as promotional kind of thing. So I guess they were proud of it, as was I. And 22 years later, when Bill Thomas, who had risen from city editor to editor, retired from the paper, they ran a long commemorative piece about him, which lead off with the story about my story, as an example of Bill’s creative innovation. One reporter called it “a shot fired across the bow of traditional journalism.”

The Diggers never called back.

Anyway, here’s the text of the piece, followed by the actual newsprint version, followed by an excerpt from the Bill Thomas retirement story, followed by my five earlier Haight-Ashbury pieces that the Diggers couldn’t stand.

The Los Angeles Times, Monday, October 30, 1967

SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE HAIGHT-ASHBURY

IN THE WEEK THAT FOLLOWED THE DEATH

OF CHOCOLATE GEORGE

“I don’t know why Chocolate George was an Angel … you couldn’t imagine him listening to rock and roll. Maybe Bach.” — Dan McDermott, who met him once

PART ONE: SPEED KILLS

(Wednesday afternoon, communion time at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, a block from Haight St., San Francisco. A communion, however, not of All Saints’ confirmed, well-dressed and officially registered church members, but her unconfirmed, robed and bearded parishioners of the street. Their bread, hardly the unleavened product of convent bakeries, is earthy and overflowing, rich with honey, nuts and raisins, officially unblessed and baked by the hippies themselves in 2-pound coffee cans. In a nearby Sunday school room, the Rev. Leon Harris, smiling and confident in this his 19th year as pastor, sits down to chat.)

FATHER HARRIS: Yes, it’s been a busy summer. As things worked out, matters have not been as bad as we had feared they might be. But the invasion has been considerable and it has been troublesome. There have been far more people in this neighborhood than there ought to be, and any afternoon or evening you can walk down the street and the crowd is just so thick you can hardly get through. Just like carnival time in a little Midwestern town, you know, and everybody comes in from miles around and crowds the street.

(Peter Krug sits on the top of a box in the back of a psychedelic shop he owns called Wild Colors, 1418 Haight. His hair is bushy and his shirt is flowered but relatively calm. He is doing chores, at the moment applying shellac to some driftwood marijuana roach clips hanging from a clothesline. While he talks, he never stops working.)

KRUG: Oh yeah, it’s really wretched and degenerate now. For one thing, they’ve been running all these sensational articles in newspapers all over the country about the Haight-Ashbury and how everybody just sits around taking drugs and having sex and everything. So all these people, all these kids all over the country, say, “Oh boy, sex and drugs, that sounds like fun.” And they come in here, you know, and they have no idea of the spirit of the neighborhood, the kind of community we had a year ago.

Then there’s all these college boys. They heard that this is a free love community and figure they can just pick up a girl on the street. They can’t, so prostitutes have come up from the Tenderloin to cash in on the demand. It’s just sort of unpleasant to be around.

FATHER HARRIS: During the summer we’ve had more of the young kids, and they’re an embarrassment to the real hippies. They get in the hair of the real hippies. The real hippies are actually a very serious-minded people. Just now one of the genuine hippies was talking to me and he was very concerned over this influx of the young children. And he said to me — you know, this could become the biggest lunatic asylum in the world. And I said yes, we’ve gotten to the point where it’s going to go one way or the other.

“Hippi-Kits: Flowers – bells – chants – flutes – headbands – incense burners – skin sequin – feathers, $4.50” — advertisement in the San Francisco Oracle, Vol.1, No. 9.

FATHER HARRIS: Then a lot of these kids when they arrive have no place to go, and we opened a community affairs office here in the church to find overnight accommodations for them. There’s another group called the Switchboard that’s become very important. It’s an information center and clearing house and crash-pad agency. I think that probably our community affairs office is going to go out of business this fall and all of that will be taken over by the Switchboard.

(From a modest flat at 1830 Fell St., facing the free feed area of the Golden Gate Park Panhandle, the Switchboard plugs into the Haight-Ashbury community. Its three office rooms and six phones serve as an instant electric grapevine — dispensing for one thin hippie dime free legal aid, free housing, free food and the latest information on what’s happening and where to get help.

(In the front room, Dan McDermott is working the housing office desk, casually rummaging through an index file of crash pad locations. Near the desk sits another volunteer, Kathy Rimley, and across the room, at the far end of an overstuffed couch, a middle-aged Negro woman cries quietly. She is from Los Angeles and has just volunteered to cook at a free food kitchen in a desperate effort to find her son.)

MISS RIMLEY: It’s changed, it’s really changed.

McDERMOTT: Attracted hoods. Girls being almost attacked in the park here, threatened. The free love thing, being misinterpreted as free sex instead of free love. A lot less respect than there was. There are a lot of takers. Like, they know there’s free food, and they know there’s free housing, and they sit back and say, “Do it for me. It’s your job.” We don’t dig that, but we’re not going to turn them away either.

MISS RIMLEY: Haight St. used to be a real nice thing to walk down, but it’s ugly now. I don’t enjoy it. And like, the streets are so dirty, you’re disgusted to walk barefoot down them. Really, I’m scared I’ll pick up a disease. The streets are just black with dirt, and this is from people literally living and eating and throwing up and killing on the street.

“It was a beautiful day for a funeral — Hells Angels style. No tears, no black crepe, no sad songs for Chocolate George Hendricks, dead of a basal skull fracture at age 34.” — San Francisco Chronicle, Tuesday, Aug. 29,1967

KRUG: To give you an idea of some of the changes. For instance, a year ago there was a great deal of giving and sharing among the people who lived here. But a year ago the giving was initiated by the giver; now it’s initiated by the receiver. People are demanding things from you instead of offering things to you. And the education level in the neighborhood has gone down considerably.

(Haight St. itself. A bearded underground newspaper vendor with bad teeth is approached by a similar young salesman in a Daniel Boone buckskin jacket.)

BAD TEETH: Your big chance — your big chance, folks, for a gen-you-wine Haight-Ashbury newspaper. Take one back to the family.

DANIEL BOONE: You want to know something, there’s no such thing as gravity.

BAD TEETH: There ain’t?

DANIEL BOONE: It’s in your mind. In about three minutes you could be this high off the ground.

BAD TEETH: Well, I didn’t think there was any gravity when I was born, but I didn’t float. I didn’t float and I didn’t know there was any gravity.

DANIEL BOONE: I mean, what is gravity, anyway?

BAD TEETH: What’s radio?

DANIEL BOONE: Another thing is electricity.

BAD TEETH: Yeah.

DANIEL BOONE: I think that when you turn on the radio, you create the music with your own mind. I honestly believe that. The idea that some guy behind a mike is talking to you 6,000 miles away — isn’t that ridiculous?

BAD TEETH: That’s not — they don’t have — radio — radio doesn’t go through wires.

DANIEL BOONE: Huh?

(Between Masonic Ave. and Stanyan St., five blocks, at least 50 hippie hawkers have turned out this afternoon to greet the tourists. They are selling everything from paper flowers to instantly penciled poetry, but mainly they are selling the latest editions of the local psychedelic press.

(One vendor seems to be doing particularly well, an older man, squat, huge-nosed, wearing yellow spectacles and a purple jersey, standing near a sidewalk snack bar that advertises LOVEBURGERS.)

VENDOR: In the Haight area you really can’t make a great amount ’cause there’s too many people selling papers. But I usually go down to Chinatown. I have a particular spot in front of the Trade Center which sells very, very well. I’ve made as hight as $55 in one day. Sundays I make $35, $40, about 300 papers. The Oracle is the best paper that we sell. I usually have three papers, the L.A. Oracle, the San Francisco Oracle and the Haight-Ashbury Maverick, and then sometimes on Fridays the Barb, the Berkeley Barb.

I don’t even come up to Haight St. anymore. Today is the first time I’ve been here in two weeks. The street is, like, turning into a real zoo, I guess you could call it. Kids come in , put on their mothers’ old dresses or coats and are hippies for the weekend.

The only reason I’m up here today and not in front of the Trade Center is some kids went down and stole my spot. But I’ll go back maybe Sunday or something like that.

(A half block away, at 558 Clayton St., the Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic’s daily hepatitis bus is leaving with four jaundiced patients for San Francisco General Hospital. Today is foot day at the free clinic, and inside, perhaps 20 barefoot hippies with blisters and sprained ankles wait in line to see a young volunteer foot specialist during his weekly visit.

(In the kitchen at the rear, Papa Al Graham, 42-year-old senior adviser for the clinic, and Peter Schubart, 19-year-old clinic administrator, take a rare coffee break.)

PAPA AL: Chocolate George was a very interesting person. Nice to the kids here, he’d stop and talk to almost anybody. The kids sort of related to him in a way more than they do to most of the Angels.

He seemed to be looking for something — I don’t know, almost everybody is up here. But he gave me a personal impression that he was very lost and very much seeking something he could relate to.

By the way, I think one thing, with all honesty, that people in newspapers ought to do is realize the seriousness of what’s happening here and throughout the United States. What’s happening to these kids is not good and it’s not finny — the whole narcotics scene, the whole dope scene, the whole rundown.

SCHUBART: In general there’s been a sharp upsweep in methedrine use — speed — which is a bad scene because it’s very psychologically addictive. It’s destructive physically and it make the people who shoot speed really paranoid and up-tight. They get very touchy and edgy and are liable to fight with people. And this is completely the opposite of what you get with LSD or marijuana.

There are generally two categories of people, the people who do use methedrine and the people who don’t, and there’s very little in the middle. There’s a line somewhere about using a needle; either you can hack it and you like it, or else you can’t stand it at all and it’s a repulsive thing. So you have the people on one side of the line campaigning strongly against it, saying speed kills, and the people on the other side of the line shooting up.

PAPA AL: We get kids selling bad speed, which is actually dangerous. It might have strychnine in it, for example. They want to cut it, they want to make more money. Yeah it’s sick, this is what I’ve been telling you. We’ve had speed in here with almost anything you can think of in it — sugar, salt. It’s absurd in a way because methedrine is very cheap to make. But wherever you’re going to make money, you’re going to want to make another buck. You know, that whole scene.

SCHUBART: When people eat beans and rice and live out in the park or on a street and take a lot of drugs, their resistance goes down. Our patent load is running between 110 and 160 a day, mostly things secondary to bad nutrition. Respiratory infections, gastro-intestinal, dermatological problems. We have a few bad trips and drug reactions. We’ve established a regular hepatitis bus going out to the county hospital, and it’s never been empty yet.

(Having finished his roach-clips, Krug — still on the box in his psychedelic shop — starts folding flat pieces of pre-scored cardboard into long, thin, empty brown boxes. He turns out five a minute.)

KRUG: Well, there haven’t been any big riots. I don’t go out on the street at night much ’cause it’s so unpleasant — people urinating in the doorways and sitting around drinking wine and vomiting in the gutters — so I really couldn’t say whether there’s very much violence; but I think there’s probably a lot more likelihood of it than in the past.

Oh yeah, there was Carter who got killed by some mentally ill fellow who stole his $3,000 and his car. And then there was this other guy, Superspade, who got killed, and he just made the mistake of letting the wrong people know that he had $30,000 in cash in his apartment. He was a very large scale dealer.

It’s sort of unfortunate; since people have discovered that there’s lots of money to be made in this scene, all sorts of unpleasant folks have been coming in.

McDERMOTT (Switchboard): We had a Death of Money parade last November, and it was led by Chocolate George and Candy, another Angel. That was when I met Chocolate. They led the parade and they were the only two who gut busted.

I don’t know why Chocolate George was an Angel. He was a short, very stocky guy; you might call him Rock if you didn’t know his name. He had a bit of a beard, not very long hair, down to the base of his neck. He was calm. By calm I mean you couldn’t imagine him listening to rock and roll. Maybe Bach. Well, that’s my own opinion, ’cause rock and roll is kind of nervous. He wasn’t nervous.

KRUG: Actually, I think the turning point was probably the be-in last January. Suddenly there were 25,000 weird people out in Golden Gate Park, and they had the write-up in Newsweek magazine, and for the first time the whole country was conscious of the neighborhood and how big the hippie thing was. And it’s sort of hard to keep the Utopian situation going when everyone is watching you.

So that’s when the tourists started coming. And it also made people very self-conscious because hippies themselves realized for the first time how many of them there were. And people who had never thought of anything except having a happy life and enjoying life with their friends and learning about themselves, who had never thought of themselves as any part of a movement, started thinking in terms of cultural revolution and taking over the world.

But it was in February, I guess, something happened that really sort of wrecked the spirit for good. We had a big hassle between the merchants and the Diggers, which was the first conflict within the community that had ever occurred. For the first time a group from the neighborhood was trying to impose their ideas on other people.

The Diggers demanded that all the shops on Haight St. go co-op, which was sort of ironic because just about everybody at that time was making about 50 cents an hour. And some Diggers were threatening to dynamite stores if they didn’t go co-op. Anyway there was this big conflict and the spirit of the neighborhood was never the same after that. A lot of people left right then.

FATHER HARRIS: The Diggers have sort of deteriorated to a considerable extent. They were very loosely organized, in fact they prided themselves on not having any organization at all, and they were experiencing considerable difficulty ih administering their office here.

So the Diggers themselves closed the office. The Digger houses were all closed by the Health Department. But again, the Diggers could have taken care of the Health Department demands if they had been able to pull themselves together.

“JIMMY JACKSON, you are delinquent, do you know that? It’s against the law for 15-year-olds to be alone. Come home. Love, Your Father.” — classified ad in the Haight-Ashbury Free Press, Vol. 1, No. 1.

PAPA AL: They’re lost. They’re bewildered. They don’t understand what’s going on with the big world around them, the confusing world. So it’s understandable that they are looking.

But what’s good about coming and living in communities where they don’t have money, where they have to panhandle, where they have to do anything to get a few cents, where they don’t eat well, where they live in filth and dirt?

What’s good about it? Northing, in muy opinion.

McDERMOTT: I was working the desk when the information came in, and it had just happened seconds before. And it was at Cole and Haight. Four Angels had just come down Shrader, made a right turn, and Chocolate got hit. Two of the Angels carried him off the street, and another Angel went over and took the guy out of the car and said, “Calm down. It’s not your fault.”

That was the immediate information I got. I don’t know if it’s true or not.

PART TWO: DIASPORA

FATHER HARRIS: Now earlier in the summer, when there was a prospect of a really massive invasion so serious as to produce riots, there were posters put up around the neighborhood by hippies urging people to go elsewhere because of the imminent catastrophe. These posters said, after all, Haight-Ashbury is anywhere, it’s not just here. And so, go to the mountains, go to the seashore, go to the woods; have Haight-Ashbury there. And some did.

(A blue sedan speeds north toward Sebastopol on an overcast Highway 1, skirting the eastern shore of Tomales Bay. Charlotte Lyons and Bryce Gray are off to visit their friend Dave at a hippie communal ranch called Morning Star. Dave lives in a tree house there that he built himself. Charlotte and Bryce live in Forest Knolls near San Anselmo, in a sylvan mountain cottage with spiring pines and a real brook in the front yard. Until April they lived in the Haight-Ashbury, but they moved because things got up-tight.)

CHARLOTTE: And because of the buses going by all the time and the tourists, and the whole thing became really a lot more commercialized.

BRYCE: There’s even a topless place there now on Haight St.

CHARLOTTE: Lot of people going to other places. Places like Morning Star and, like, there’s a ranch in Big Sur where a friend of ours is staying. He’s on the side of a hill, and there are 60 or 70 people living there in adobe houses and eating really well — having corn and brown rice and meat sometimes, and the wild turkeys living around there that they catch and kill.

BRYCE: Maybe 100 to 150 people live at Morning Star, and out of those, maybe 30 will be permanent. They run the farm as sort of a way station so people can come up and live out in the country and see what it’s like. They keep it going, they grow the vegetables and everything. They don’t try to produce more than they need.

(The boxes folded, Krug starts fiddling with a bowlful of wet, dingy jewelry.)

KRUG: These are pearls, junk jewelry pearls. And somebody explained to me that if you soak them in vinegar a couple of days, you can peel off the plastic coating and there are these nice little white glass beads underneath.

At any rate, most of the best people have left here. The ones that stayed in the city have gone to the Mission District; there’s a little park right around the corner from Army St., Army and Fulton or Howard or Harrison, something like that; there are more hippie-type people in the Mission District now than there are in the Haight-Ashbury.

And the ones who have left the city have moved out to the country, Sonoma County and places like that. There are a lot of little communes opening up, scattered all over the countryside in Northern California.

We decided just last night that we’re going to move to the other side of the hill here, 12 blocks south where it’s still peaceful and calm.

(Charlotte and Bryce have arrived at Morning Star. They leave their car at the foot of a giant white telephone-pole cross and begin trudging up a dirt entrance road that winds into the mountains. After a quarter mile, dozens of improvised huts and shacks appear on each side of the road. Some are made of discarded cardboard, others of twigs, cloth and canvas; and a few, prepared to withstand the huff and puff of winter, are built of lumber and aluminum siding.

(Beyond a clearing at the end of the road, Charlotte and Bryce come upon Dave, standing thin and tan and totally naked at the base of his tree house. The sun is starting to set behind the hills, and in the distance dogs are barking.)

DAVE: There’s only about half as many people here as there were a couple weeks ago.

CHARLOTTE: How come?

DAVE: I don’t know. There’s little sub-cultures starting, like people living in one area and supporting themselves — small tribes. Every once in a while a small tribe will leave for someplace much further away from people, where they can really be together.

Whatever you get out of it is entirely up to you. I mean, the only reason I’m staying here is because I started this tree house and got far enough into it that it might provide enough shelter to stay this winter. And I’m perfectly happy. It’s conceivable that tomorrow I won’t be, in which case I may go someplace else like, you know, top of the Rocky Mountains.

(A priest of another collar enters the Sunday school room of Father Harris. Tossing his homemade, mimeographed missal on the table, the black-bearded young man eagerly introduces his new religion.)

PRIEST: Onnow is meaning. It’s a program of meaning. Basically, I am the originator or founder, you might say, of Onnow — the word.

Brandy is the name that I go by. I’m 24.

I love the city and I love the ocean and I love to skin dive and I love the forest and I love to camp. And I don’t feel the need to choose, you know, at any one point, to belong wholly forever to any one of those domains; they are all earth. I love the whole earth.

My father’s dead — he died when I was seven in a hunting accident — and my mother is living in Pasadena and doesn’t know where I am. (He giggles.) That’s a common situation for many of the people that are up here, I think. Many of the people that are up here have many people who don’t know where they are.

It doesn’t bother me very much. I know pretty much where my mother’s at now, and it’s fine; and I hope she’s at peace, and I hope she’s finding enjoyment, and my 16-year-old brother’s turning on, and I wonder if she knows it yet.

“George did not look like himself. He looked like a Russian saint. Over his long hair and combed mustache and beard was a huge Russian fur hat, on it an iron cross. The Hell’s Angels leather vest was draped over the satin lid of the casket. Peace and love buttons covered his chest.

“There was a corner of the chapel that was not visible until one stood right before George. There, hidden by curtains from the rest of the room, sat the family. The old world of black raiment and red, swollen eyes.” — The Haight-Ashbury Free Press, Vol. 1, No. 1.

PART THREE: DESIDERATA

CHARLOTTE: A lot of the hippie movement has to do with change, and accepting changes and being a lot more tolerant of the things that are going on. And I don’t think hippies are as paranoid of dying.

(After arranging the boxes in neat rows across the top of his workbench, Krug begins stuffing them with crisp white printed scrolls, one of which he now unrolls for examination)

KRUG: This is the Desiderata, a hundred word or so statement of philosophy. If there is any hippie philosophy at all it’s pretty close to this. It was found in a church in Baltimore in 1690, and it’s very much like 19th century American transcendental philosophy — Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman — sort of mystical, pantheistic. We sell it for a dollar.

“It was a kind of last run that Charles George Hendricks Jr. would have dug.

“George, or Chocolate — he was known as both — was a mechanic by trade who had worked for the Recreation Center for the Handicapped for the past 12 years.” — San Francisco Chronicle, Aug. 29.

“Go placidly amid the noise & haste, & remember what peace there may be in silence. As far as possible without surrender be on good terms with all persons.” — Desiderata, found in Old Saint Paul’s Church, Baltimore, dated 1692.

CHARLOTTE: There really is a big difference between hippies and straight people. I mean, we spend all our time sitting around smoking dope, I mean really a lot of time; and they spend all their time sitting around taking coffee breaks and working. They’re goal oriented, and we really aren’t.

BRYCE: I’ve never been completely content with any kind of material possession I’ve had. As soon as I get something, there’s always the want for something a little bit bigger, better. The same thing with money; so I’d rather forget about it altogether. I guess one of our ultimate aims is to get technology advanced to a point where you don’t need people to work, where everyone can be free.

CHARLOTTE: I really believe in forces. Everything I’ve ever wanted, little things and big things, they’ve always come true. Since I was little I’ve wanted to live on a farm and have sheep and bake bread every day, you know? And have an apple orchard and a vineyard and big dogs and lots of children. And that’s pretty much what I’m in now. Quite naturally everything has always happened quite well.

“Be yourself. Especially, do not feign affection. Neither be cynical about love; for in the face of all aridity and disenchantment it is perennial as the grass.” — Desiderata.

(Seated on his back porch rocker at Morning Star, folksinger Lou Gottlieb, owner of the ranch and former member of the Limelighters, lectures a class of hippies on Buddhist thought. His beard is thick, his voice rich and resonant, flowing through the trees and tall corn at the edge of the twilit clearing.)

GOTTLIEB: Man was loving God and had forgot all about his brother man. The man who in the name of God could give up his life could also turn around and kill his brother man in the name of the same God. That was the state of the world. Men would sacrifice their sons for the glory of God, would rob nations for the glory of God, would kill thousands of beings for the glory of God, would drench the earth with blood for the glory of God. Buddha was the first to turn their minds to the other god, man.

“Take kindly the counsel of the years, gracefully surrendering the things of youth.” — Desiderata.

FATHER HARRIS: I feel I’ve been personally enriched through the contacts I’ve had with many of these people. Of course, our philosophies are at variance on many points. But I’ve met some who are nevertheless extremely intelligent people and highly estimable people, and in many cases, better people than I am.

They are becoming more and more interested in the church. I don’t think that the interest is going to result in anything phenomenal in my time, but one of the leading hippies in the community did have his wedding here last Sunday. It was a bang-up affair, everyone in typical hippie garb. It was the first time I ever married a bride with bare feet.

It’s hard to say about the future; it’s a very fluid situation. It could become, as this man feared, the world’s biggest lunatic asylum, or it might become the center of a new society that will revolutionize the country.

It’s amazing how the things that I’m aiming for in my business and the things the hippies are aiming for are actually the same. They are concerned with love and sharing of property with others, blessings, generosity, appreciation of true values such as justice and peace. And that’s Christian all the way through.

“Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself. You are a child of the universe, no less than the trees & the stars; you have a right to be here. And whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should” — Desiderata.

KRUG: These are pearls, junk jewelry pearls. And somebody explained to me that if you soak them in vinegar a couple of days, you can peel off the plastic coating and there are these nice little white glass beads underneath.

“Therefore be at peace with God, whatever you conceive Him to be, and whatever your labors & aspirations — in the noisy confusion of life keep peace with your soul. With all its sham, drudgery & broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world. Be careful. Strive to be happy.”

POSTSCRIPT

Earlier this month police began a series of nightly “sweep-ins” through the Haight-Ashbury, checking IDs, frisking, arresting suspected juvenile runaways and other hippies they felt were a public nuisance.

According to a Switchboard spokesman, however, most of the younger, plastic hippies had already left when schools opened in mid-September, and the raids are simply part of a new policy of “police harassment.” A group of clergymen and professors is presently seeking to have the raids stopped, he said.

Also this month, Sonoma County officials ordered Lou Gottlieb to stop “operating a camp without a license,” and the health department condemned most of the structures at Morning Star. The Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic closed for lack of funds, but is expected to reopen this week.

And the Psychedelic Shop, the first hippie enterprise in the Haight-Ashbury and the only one to go coop at the Digger’s request, officially went out of business, reportedly $6,000 in debt.

Click on the images below to read the originals:

Editor’s Legacy : Good Writing, Long Stories and Freedom

January 01, 1989|DAVID SHAW | Times Staff Writer

Noel Greenwood can still remember the hoots of derision and confusion he heard at The Times in 1967 when he was a new reporter here and the paper had just published a colleague’s lengthy, impressionistic account of hippie life in the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco.

Reporter David Felton had spent six weeks on the story, and when Greenwood came to work the morning it was published, he found many of the paper’s veteran reporters muttering about the judgment–if not the sanity–of William F. Thomas, the metropolitan editor, who had assigned and approved the story.

Felton is a gifted and stylish writer, and on the Haight story Thomas had told him, “Don’t be afraid to try something different . . . take risks.” Sure enough, Felton had produced a 6,000-word blend of hippie dialogue in quasi-dramatic form, punctuated by his own observations, written almost as stage directions and presented in italics and parentheses.

‘Down the Toilet’

“The older reporters . . . thought that the newspaper had gone down the toilet,” said Greenwood, now a deputy managing editor at The Times. “They thought that Thomas had lost his mind. . . . What was this strange piece doing in the paper? And why in the world would you need (several) . . . weeks to do a story?”

But Greenwood admires both Thomas and Felton (who is now a movie and television writer), and he saw Felton’s story as a “shot fired across the bow” of traditional journalism.

Indeed it was.

Thomas officially retires today, five months shy of his 65th birthday, after 32 years with the Times Mirror Co., including six years as metropolitan editor and the last 17 years as editor of The Times; two decades after Felton’s story was written, it remains symbolic, in a way, of both Thomas’ tenure and his legacy.

velpz1

It’s Hamster Kombat We’re just getting started, but we already know for sure that the listing is a go! And very soon

You are now the director of a crypto exchange!

Tap on the screen, develop your business and earn coins.

And if you get your friends involved, you’ll build a cool business together and earn more coins

https://t.me/hamster_kombat_bot?start=kentId5804119175

Thimbles : Plongee dans un Univers de Jeu Exceptionnel

Bienvenue dans le monde fascinant de Thimbles Casino, un etablissement de jeu en ligne ou le divertissement et l’excitation se rencontrent pour creer une experience inoubliable. Que vous soyez un joueur chevronne ou un novice enthousiaste, Thimbles Casino offre un eventail impressionnant de jeux et de fonctionnalites concues pour captiver et satisfaire toutes vos attentes.

Une Plateforme de Jeu Moderne et Innovante

Thimble Casino se distingue par son approche moderne et elegante du jeu en ligne. Des votre arrivee sur le site, vous serez accueilli par une interface raffinee qui combine design et fonctionnalite. Le design epure facilite la navigation et vous permet de vous concentrer pleinement sur l’experience de jeu.

Le site de thimbles est concu pour offrir une experience fluide et sans interruption, que vous jouiez sur un ordinateur, une iPad ou un smartphone. La plateforme est compatible avec tous les principaux navigateurs et systemes d’exploitation, garantissant un acces facile et pratique a vos jeux preferes, peu importe ou vous vous trouvez.

Une Gamme Variee de Jeux pour Tous les Gouts

Au c?ur de Thimbles Casino, vous decouvrirez une vaste collection de jeux, chacun offrant une experience unique et passionnante. Le jeu de gobelets, egalement connu sous le nom de Thimbles game, est l’un des jeux phares du casino. Ce jeu captivant met a l’epreuve votre concentration et votre capacite a suivre le mouvement des jetons sous les gobelets. Avec des regles simples mais un gameplay addictif, le jeu de thimbles est un choix populaire parmi les joueurs a la recherche de defis stimulants.

En plus du jeu de thimbles, Thimbles Casino propose une large selection de jeux de slots, allant des classiques a trois rouleaux aux machines a sous sophistiquees avec des images 3D impressionnants. Les jeux de slots sont dotees de diverses fonctionnalites bonus, telles que des spins gratuits, des multiplicateurs et des jackpots progressifs, offrant de multiples opportunites de gagner gros.

Les amateurs de jeux de cartes ne seront pas en reste avec une gamme complete de jeux tels que le jeu de cartes, la roulette , le baccarat et le poker. Chaque jeu est concu pour offrir une experience immersive et intense, avec des regles claires et des graphismes. Les tables sont animees par des croupiers, creant une atmosphere de casino realiste qui vous transporte directement au c?ur de l’action.

Thimble Casino : Une Experience Personnalisee et Exclusive

Pour ceux qui recherchent une experience de jeu plus personnalisee, Thimble Casino offre des options uniques et des offres speciales. Le casino propose une variete de bonus de bienvenue, de offres regulieres et de programmes de loyaute concus pour recompenser les joueurs fideles et offrir des avantages supplementaires.

Site officiel: https://33.staikudrik.com/index/d1?diff=0&utm_source=ogdd&utm_campaign=26607&utm_content=&utm_clickid=snqcg0skg8kg8gc0&aurl=http%3A%2F%2Fleansolutions.co%2Fblog%2Fthimbles-gagnez-de-largent-reel-en-jouant-dans-les-casinos-en-ligne%2F&member%5Bsite%5D=https%3A%2F%2Fggslotwallet.com%2F&member%5Bsignature%5D=%3Cspan+style%3D%22font-weight%3A+700%3B%22%3EThis+online+game+actually%3C%2Fspan%3E+consists+of+the+consumer+having+to+pay+to+get+a+%22slot+card%22+which+is+actually+a+chip+that+has+to+be+positioned+on+the+slot+machine+for+the+sport+to+start.+In+the+course+of+the+free+spins%2C+77+wild+substitutes+will+offer+extra+chances+to+kind+profitable+combination+on+this+online+slot+game.+Along+with+this%2C+there+will+probably+be+bar%2C+golden+bells+and+stars+that+may+aid+you+in+winning+big+prizes.+It+is+necessary+to+notice+that+it+is+that+this+slot+machine+which+will+determine+the+%22winning%22+game+that+the+player+will+get+to+play.+Each+of+the+slot+games+you+possibly+can+play+free+of+charge+on+our+site+have+a+special+theme.+An+Austrian+company+that+has+been+producing+wonderful+slot+video+games+since+the+1980s.+Slots+similar+to+%E2%80%98Secret+Elixir%E2%80%99+and+%E2%80%98Aztec+Treasure%E2%80%99+take+you+world+wide+when+you+sit+in+front+of+your+computer+or+cell+machine%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+Once+the+slots+that+they%27ve+paid+for+has+been+played%2C+then+there+is+nothing+else+to+do+except+to+wait+until+the+time+as+a+way+to+play+again.+Consequently%2C+the+primary+problem+of+many+players+is+that+once+they+have+made+the+selection+to+play+the+online+slot+video+games%2C+they+cannot+assist+however+turn+out+to+be+a+bit+pissed+off.+At+this+point+I+used+to+be+prepared+to+cut+the+entrance+half+of+the+globe+off%2C+however+I+wanted+a+method+to+add+a+little+bit+of+strength+do+it.+I%27ll+download+The+Cuckoo%27s+Calling+to+my+Kindle+%28to+read+out+in+my+hot+garden+with+a+bit+of+luck%21%29.+The+slot+additionally+gives+a+gamble+characteristic%2C+which+is+able+to+have+you+guessing+the+coloration+of+the+subsequent+randomly+generated+card.+This+card+will+enable+your+private+pc+to+be+hooked+up+with+a+network+or+wireless+network.+Three+Black+Cats+within+the+active+line+will+multiply+your+wager+by+200%2C+4+cats+-+by+1000%2C+and+5+cats+-+by+5000.+The+Kolobok%2C+one+other+%22wild%22+image+which+replaces+any+of+the+symbols%2C+apart+from+the+Black+Cat+and+stoves%2C+will+multiply+your+bet+by+100%2C+500+or+2000.+3%2C+4+and+5+rolling+pins+and+dough+in+a+row+within+the+energetic+line+will+multiply+your+wager+by+2%2C+3+or++%3Ca+href%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fggslotwallet.com%2F%22+rel%3D%22dofollow%22%3E%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%A5%E0%B9%87%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A5%E0%B8%97%3C%2Fa%3E+%3Cspan+style%3D%22font-weight%3A+bolder%3B%22%3E10%2C+respectively%3C%2Fspan%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cspan+style%3D%22font-weight%3A+600%3B%22%3EOLEH+SEBAB+ITU+KAMI%3C%2Fspan%3E+MENYEDIAKAN+LIVECHAT+SELAMA+24+JAM+SEHARI+TANPA+LIBUR+UNTUK+MENANGANI+MASALAH+YANG+DI+HADAPI+OLEH+PARA+MEMBER+KAMI.+Sebagai+inovator+dalam+industri+slot%2C+Spadegaming+memimpin+pengembangan+seluler+sejak+tahun+2013+dengan+memproduksi+sport+yang+dapat+dimainkan+di+semua+pill+dan+smartphone.+Selain+bertema+menarik+video+games+ini+di+produksi+dengan+teknologi+graphic+yang+bagus+sehingga+terlihat+seperti+kenyataan.+Consumers+cannot+do+a+lot+to+immediately+prevent+such+compromises+as+a+result+of+they+don%27t+management+the+affected+software%2C+whether+or+not+that%27s+the+software+in+POS+terminals+or+code+present+on+e-commerce+websites.+Lately%2C+POS+distributors+have+started+to+implement+and+deploy+point-to-point+encryption+%28P2PE%29+to+safe+the+connection+between+the+card+reader+and+the+payment+processor%2C+so+many+criminals+have+shifted+their+attention+to+a+special+weak+spot%3A+the+checkout+process+on+e-commerce+web+sites.+You+can+too+choose+to+only+shop+on+web+sites+that+redirect+you+to+a+3rd-party+payment+processor+to+enter+your+card+particulars+as+an+alternative+of+handling+the+info+assortment+themselves.+This+is+a+good+technique+if+you%27re+completely+uncertain+concerning+the+processor+of+the+system+you%27re+dealing+with+-+discover+older+predecessors+that+could+be+better+documented%2C+or+very+comparable+merchandise.+While+it%27s+all+the+time+good+to+have+an+up-to-date+antivirus+program+installed%2C+do+not+anticipate+that+it%27s+going+to+detect+all+web+skimming+assaults%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+Although+some+massive+retailers+and+brands+have+fallen+victims+to+web+skimming%2C+statistically+these+attacks+are+inclined+to+affect+small+online+merchants+more%2C+as+a+result+of+they+haven%27t+got+the+sources+to+spend+money+on+costly+server-aspect+security+solutions+and+code+audits.+Since+web+skimming+entails+malicious+JavaScript+code%2C+endpoint+security+programs+that+inspect+net+traffic+contained+in+the+browser+can+technically+detect+such+assaults.+The+deadline+for+complying+with+the+brand+new+requirement+has+been+extended%2C+but+many+European+banks+have+already+applied+the+security+mechanism.+Services+like+Google+Pay+and+Apple+Pay+use+tokenization%2C+a+mechanism+that+replaces+the+true+card+quantity+with+a+short+lived+number+that%27s+transmitted+to+the+merchant.+Use+digital+card+numbers+for+on-line+shopping+in+case+your+financial+institution+provides+them+or+pay+along+with+your+cell+phone.+In+case+your+financial+institution+presents+app-based+mostly+or+SMS-based+mostly+notifications+for+each+transaction%2C+flip+the+characteristic+on.+Monitor+your+account+statements+and+activate+transaction+notifications+if+supplied+by+your+financial+institution.+Use+a+debit+card+hooked+up+to+an+account+where+you+retain+a+limited+amount+of+cash+and+may+refill+it+simply+when+you+need+more%2C+as+an+alternative+of+utilizing+a+card+hooked+up+to+your+main+account+that+has+most+or+all+of+your+funds.+Many+issues+ought+to+be+taken+into+account+when+deciding+what+elements+to+buy&pushMode=popup

Le programme de recompenses de Thimble Casino est particulierement apprecie, offrant des cadeaux sous forme de points que vous pouvez echanger contre des credits, des offres ou des cadeaux exclusifs. En tant que membre du programme de fidelite, vous beneficierez egalement d’un acces prioritaire a des evenements et a des competitions, ajoutant une dimension supplementaire a votre experience de jeu.

Thumbles Casino : Une Plateforme Dynamique et Attrayante

Pour les joueurs en quete d’une ambiance dynamique et d’options diversifiees, Thimbles est le choix ideal. Ce casino en ligne se distingue par ses jeux varies et ses options nouvelles. Le site propose des jeux speciaux et des promotions speciales qui ajoutent une touche unique a votre experience de jeu.

Le casino met egalement en avant des competitions regulieres ou vous pouvez tester vos competences contre d’autres joueurs et tenter de remporter des prix attractifs. Les tournois sont concus pour etre a la fois intenses et divertissants, offrant une opportunite de montrer vos talents tout en vous amusant.

Une Securite et une Fiabilite Optimales

La securite en ligne est une priorite absolue chez Thimbles. Le casino utilise des technologies de cryptage avancees pour proteger vos informations personnelles et vos transactions financieres. Vous pouvez jouer en toute confiance, sachant que votre protection est assuree par des protocoles de securite rigoureux.

En outre, Thumbles Casino est licencie et controle par des organismes de regulation, garantissant que toutes les operations sont conformes aux normes de qualite de transparence et d’equite. Les jeux sont regulierement controles pour assurer leur integrite, et les issues sont generes de maniere hasardeuse pour offrir une experience juste a tous les joueurs.

Conclusion : Un Choix Ideal pour les Amateurs de Jeu

En resume, Thimble Casino est une destination de choix pour les amateurs de jeu en ligne a la recherche d’une experience enrichissante et variee. Avec une large choix de jeux, des bonus interessants et une protection, ce casino en ligne se distingue comme une destination de premier choix dans l’industrie du jeu. Que vous soyez attire par le jeu de thimbles, les machines a sous ou les jeux de table classiques, Thimble Casino offre tout ce dont vous avez besoin pour une experience divertissante.

Thimble Casino ajoute une dimension vivante a cette experience, avec des promotions uniques et des jeux qui promettent de garder votre interet eveille. Avec des choix de jeux varies et un engagement envers la securite et la honnetete, Thimbles est le choix ideal pour tout joueur en quete de divertissement et de gains.

Plongez dans l’univers captivant de Thimbles des aujourd’hui et decouvrez tout ce qu’il a a offrir. Que la chance soit avec vous !

Pin Up: A escolha certa para amantes de jogos de azar

Quando se trata de cassinos online populares, o Pin Up se destaca no mercado global de jogos de azar, conquistando milhoes de jogadores em todo o mundo. Este site de apostas e amplamente reconhecido por sua interface amigavel, vasta gama de jogos, e bonus generosos. Em particular, a versao Pin Up se tornou extremamente popular entre os jogadores cazaques, destacando-se como uma das principais escolhas na regiao.

Pin Up Casino: Diversas opcoes para jogadores

O pinup oferece uma vasta selecao de jogos para seus usuarios, proporcionando que todos, desde novatos ate jogadores experientes, encontrem algo de seu agrado. A plataforma inclui slots classicos que evocam a nostalgia dos antigos cassinos fisicos, alem de jogos de mesa, como blackjack, poker, e roleta, que trazem a experiencia autentica dos cassinos para a ponta dos seus dedos. Alem disso, os jogos de ultima geracao, com graficos vibrantes e temas variados, oferecem uma experiencia de jogo cativante que envolve ate os jogadores mais exigentes.

Os ofertas especiais do Pin Up sao outro diferencial significativo para jogadores novos e veteranos. O pacote de boas-vindas e especialmente generoso, proporcionando aos jogadores uma excelente base para explorar a plataforma. Alem disso, o Pin Up oferece cashbacks regulares, promocoes sazonais, e competicoes semanais que asseguram que sempre haja algo novo e interessante para os usuarios.

Como iniciar sua jornada no Pin Up Casino

Iniciar sua jornada no Pin Up casino e muito facil e direto. O processo de registro e descomplicado, levando apenas alguns minutos para ser concluido. Apos o registro, voce tera acesso total a enorme variedade de jogos, usufruir dos bonus exclusivos, e participar das promocoes e eventos que mantem a plataforma dinamica e excitante para todos os jogadores.

Nosso site: https://50.gregorinius.com/index/d1?diff=0&source=og&campaign=4397&content=&clickid=hrx9nw9psafm4g9v&aurl=http%3A%2F%2Fafrofuturismo.com.br%2Fwp-content%2Fpin-up-cassino-jogue-e-ganhe-nos-melhores-jogos-de-cassino-online%2F&title=joellemonetcream99964&url=https%3A%2F%2Fjoellemonet.com%2F&email=jettmcguigan%40web.de++skin+color+as+this+will+help+to+your+skin+to+become+richer+&smoother__For_greasy_skin_around_the_globe_beneficial%2C_since_it_is_soaks_oil_for_till_10_hours__Give_a_gentle_massage_with_the_face_using_moisturizer_and_apply_it_on_your_neck%2C_to_see_the_perfect_image_%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0AWell%2C_even_if_essential_oils_and_wrinkles_are_strongly_connected%2C_that_doesn%27t_mean_that_all_oils_work_the_same_and_how_the_result_always_be_what_you_expect__There_are_major_differences_between_oil_types_and_you_will_know_exactly_what_you_need_it_if_you_must_cure_your_wrinkles_%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0Ahealthline_com_-_https%3A%2F%2Fwww_healthline_com%2Fhealth%2Fhow-to-get-rid-of-frown-lines_For_fantastic_cutting_back_on_the_degree_of_food_consume_at_one_setting_will_help%2C_just_be_sure_to_switch_to_five_small_meals_each_working__For_many_men_and_women%2C_they_you_should_be_affected_by_acid_reflux_when_they_eat_a_lot_food__You_can_to_still_end_up_eating_the_very_same_amount_of_food_to_perform_just_divide_it_up_throughout_the_day%2C_instead_of_eating_everything_in_2_or_3_meals_%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A_form-data%3B_name=%22field_pays%5Bvalue%5D%22%0D%0A%0D%0ABahrain%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A+form-data%3B+name%3D%22changed%22%0D%0A%0D%0A%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A+form-data%3B+name%3D%22form_build_id%22%0D%0A%0D%0Aform-c673d3ab9883a7e4fa1cec1fd3225c4c%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A+for&pushMode=popup

Alem disso, o Pin Up oferece uma serie de opcoes de pagamento que facilitam a realizacao de depositos e saques, com suporte ao cliente disponivel 24 horas para assistir com qualquer duvida ou problema que possa surgir.

Aplicativo movel Pin Up: A emocao sempre a mao

Uma das vantagens mais importantes do Pin Up e a presenca em dispositivos moveis, que assegura que os jogadores tenham acesso aos seus jogos favoritos em qualquer lugar, em qualquer situacao. O app do Pin Up esta disponivel para download em todas as principais plataformas, como Android e iOS, e e totalmente compativel para dispositivos moveis. Isso significa que voce pode desfrutar de seus jogos enquanto viaja, relaxa em casa, ou simplesmente deseja em um ambiente mais confortavel.

Com o Pin Up app, voce nunca ficara para tras nos seus jogos preferidos, pois a plataforma oferece atualizacoes constantes e alertas em tempo real sobre novos jogos, promocoes, e eventos, para que voce esteja sempre bem informado das ultimas novidades do mundo dos cassinos online.

Consideracoes finais

O Pin Up cassino online e sem duvida uma das opcoes mais completas para quem busca qualidade em jogos de azar. Com navegacao facil, uma enorme variedade de jogos, e ofertas generosas, o Pin Up proporciona uma experiencia de jogo que atende as expectativas de novatos e veteranos.

Se voce esta procurando um cassino online confiavel, que prioriza a satisfacao do usuario, o Pin Up sera a escolha perfeita para voce. Experimente o Pin Up agora mesmo e descubra porque ele e considerado um dos melhores entre jogadores em todo o mundo.

Lucky Jet — это трендовая азартная игра на платформе 1Win, которая предлагает игрокам уникальную возможность испытать свою фортуна. Это не просто игра, а настоящий квест, который сочетает в себе динамичный геймплей и возможность получать прибыль в каждом подходе.

В jet ставки каждое действие игрока имеет смысл. Умение взвешивать риски на происходящее на экране и выбирать момент, когда нужно выйти из игры, может обладать большие выигрыши. Однако, важно помнить, что каждая ошибка может аннулировать все деньги.

Игровой процесс в Lucky Jet отличается доступностью, но требует осмотрительности и развитой стратегии. После определения размера ставки игроки наблюдают за летательным аппаратом, который плавно начинает взлетать. Чем дальше он поднимается, тем значительнее становится уровень умножения, который накапливает первоначальную ставку.

Игрокам следует выбрать, когда получить прибыль. Это основной момент игры, так как слишком раннее прекращение может привести к низкому выигрышу. А позднее действие может привести к проигрышу всех средств, если самолёт внезапно выйдет за пределы и слишком поздно забрать.

Lucky Jet от 1Win предлагает своим игрокам специальные возможности воспользоваться акциями для получения экстра-призов. Эти бонусные коды могут обеспечить игрокам бонусные средства при внесении депозита или событиях. Для введения промокода, игрокам необходимо внести его в форму на сайте 1Win или в мобильном устройстве.

Для участия с Lucky Jet и использования всех опций платформы, игроки могут исследовать официальный сайт http://htmldwarf.hanameiro.net/tools/fav/digest.php?view=1&title=%E3%83%AD%E3%83%83%E3%82%AF%E3%83%B3%E3%83%AD%E3%83%BC%E3%83%AB%E3%83%8F%E3%83%8D%E3%83%A0%E3%83%BC%E3%83%B3&writer=%E9%89%A2%E3%81%95%E3%82%93&ffs=1&words_1=%E3%80%8C%E3%81%A9%E3%81%93%E3%81%8B%E3%81%AB%E8%A1%8C%E3%81%8D%E3%81%9F%E3%81%84%E3%80%8D%E3%81%A8%E5%90%9B%E3%81%8C%E8%A8%80%E3%81%A3%E3%81%9F%E3%81%8B%E3%82%89%E3%81%9D%E3%82%8C%E3%82%92%E5%8F%97%E3%81%91%E3%81%A6%E6%89%8B%E3%82%92%E5%BC%95%E3%81%84%E3%81%9F%E3%81%BE%E3%81%A7%E3%81%AE%E3%81%93%E3%81%A8%E3%81%A0%E3%80%82%E4%B8%96%E7%95%8C%E4%B8%AD%E3%81%AE%E7%89%A9%E8%AA%9E%E3%81%A7%E6%9B%B8%E3%81%8D%E6%AE%B4%E3%82%89%E3%82%8C%E3%81%A6%E3%81%84%E3%82%8B%E3%82%88%E3%81%86%E3%81%AA%E9%80%83%E9%81%BF%E8%A1%8C%E3%81%A0%E3%81%A8%E3%80%81%E5%83%95%E3%81%AF%E6%80%9D%E3%81%A3%E3%81%A6%E3%81%84%E3%81%9F%E3%80%82&words_2=%E3%80%8C%E5%85%89%E5%BF%A0%E3%80%8D+%0D%0A%E3%80%8C%E3%81%86%E3%82%93%EF%BC%9F%E3%80%8D+%0D%0A%E3%80%8C%E3%81%93%E3%82%8C%E3%80%81%E3%81%A9%E3%81%93%E3%81%BE%E3%81%A7%E8%A1%8C%E3%81%8F%E3%82%93%E3%81%A0%E3%80%8D+%0D%0A%E3%80%8C%E7%9F%A5%E3%82%89%E3%81%AA%E3%81%84%E3%80%8D+%0D%0A%E3%80%8C%E3%81%9D%E3%81%86%E3%81%8B%E3%80%8D&words_3=%E3%81%A0%E3%81%8B%E3%82%89%E3%80%81%E5%83%95%E3%81%8C%E6%8C%81%E3%81%A3%E3%81%A6%E3%81%84%E3%82%8B%E9%95%B7%E8%B0%B7%E9%83%A8%E3%81%8F%E3%82%93%E3%81%AE%E5%86%99%E7%9C%9F%E3%81%AF%E3%80%81%E5%B0%8F%E3%81%95%E3%81%8F%E3%81%A6%E5%B0%8F%E3%81%95%E3%81%8F%E3%81%A6%E3%80%81%E6%8B%A1%E5%A4%A7%E3%81%99%E3%82%8B%E3%81%A8%E9%A1%94%E3%81%8C%E3%81%BC%E3%82%84%E3%81%91%E3%81%A6%E3%81%97%E3%81%BE%E3%81%86%E3%81%BB%E3%81%A9%E5%B0%8F%E3%81%95%E3%81%8F%E3%81%A6%E3%80%82%E5%83%95%E3%81%AF%E3%81%9D%E3%82%8C%E3%81%8C%E6%9C%AA%E3%81%A0%E3%81%AB%E6%82%B2%E3%81%97%E3%81%84%E3%80%82+&words_4=%E3%81%82%E3%81%AE%E6%97%A5%E3%81%AE%E3%82%88%E3%81%86%E3%81%AB%E3%80%81%E3%81%82%E3%81%AE%E6%97%A5%E3%82%88%E3%82%8A%E3%82%82%E3%81%84%E3%81%8F%E3%82%89%E3%81%8B%E5%84%AA%E3%81%97%E3%81%8F%E3%80%81%E6%89%8B%E9%A6%96%E3%82%92%E6%8E%B4%E3%82%93%E3%81%A0%E3%80%82%E8%B5%B0%E3%82%8A%E5%87%BA%E3%81%99%E3%81%93%E3%81%A8%E3%82%82%E3%81%97%E3%81%AA%E3%81%8B%E3%81%A3%E3%81%9F%E3%80%82%E9%80%83%E3%81%92%E3%81%AA%E3%81%84%E3%81%93%E3%81%A8%E3%82%82%E3%80%81%E5%A3%B0%E3%82%92%E8%8D%92%E3%81%92%E3%81%AA%E3%81%84%E3%81%93%E3%81%A8%E3%82%82%E3%82%8F%E3%81%8B%E3%82%8A%E3%81%8D%E3%81%A3%E3%81%A6%E3%80%82&words_5=&words_6=&words_7=&words_8=&words_9=&words_10=&name=%E7%8C%AB%E8%88%8C&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwrpworld.com%2Fblogs%2Flucky-jet-krash-igra-v-1win-kazino-luchshie-strategii-i-sovety%2F&view=%E7%94%9F%E6%88%90%E3%81%99%E3%82%8B. На портале вы найдете все услуги, включая рекламные акции о Lucky Jet.

Официальный сайт 1Win представляет интуитивно понятный доступ к всем разделам. Здесь вы можете внести депозит и участвовать.

Для промокодов, посетите официальный сайт 1Win и проверяйте о специальных предложениях.

Простой и интуитивный интерфейс: Интерфейс 1Win Lucky Jet удобен и рассчитан на то, чтобы даже новые игроки могли легко познать правила и начать играть. Графика и опции очищены, что позволяет сосредоточиться на стратегии и удовольствии от игры.

Высокие коэффициенты и большие выигрыши: Lucky Jet предоставляет шанс на большие выигрыши благодаря огромным коэффициентам. Игроки могут настраивать разные уровни, что позволяет достичь большую деньги, выбрав оптимальный момент для отобрания ставки.

Динамичный и живой геймплей: В Lucky Jet игроки могут наблюдать, как самолёт увеличивает высоту, что добавляет элемент напряжения. Каждый игровой период непредсказуем, и ожидание от волнительных моментов делает игру ещё более захватывающей.

Мгновенные выплаты и безопасность: Платформа 1Win гарантирует постоянные выплаты и безопасный уровень конфиденциальности, что подарит безопасную среду для геймплея.

Lucky Jet на платформе 1Win — это восхитительная игра, которая сочетает в себе элементы непредсказуемости и анализа. Для тех, кто ищет острые ощущения и большие вознаграждения, Lucky Jet — это привлекательный выбор.

Lucky Jet — это трендовая азартная игра, представленная на платформе 1Win. В этом захватывающем игровом автомате, также известном как лаки джет, игрокам предоставляется шанс испытать удачу. Благодаря своей понятной механике и волнующему процессу, Lucky Jet привлек внимание множества любителей игр, стремящихся к крупным выигрышам и острым переживаниям. Игра сочетает в себе элементы авантюризма и анализа, что делает её привлекательным выбором для почитателей азартных игр.

Игровой процесс в лаки джет доступный, но требует осмотрительности и размышлений. Игроки начинают с выбора суммы перед началом каждого раунда. После этого, на экране появляется воздушный объект, который постепенно поднимается вверх. Задача игрока — выявить, когда именно стоит отобрать выигрыш, до того как самолёт достигнет установленного множителя.

Lucky Jet 1Win позволяет игрокам выбирать разные коэффициенты, которые могут добавлять их потенциал. Чем дольше игрок решает отобрать свою ставку, тем крупнее множитель и предполагаемый приз. Однако, если luckyjet поднимется слишком незапно и игрок не успеет прикоснуться свой выигрыш, ставка будет недоступна. Это добавляет элемент неопределенности и мышления, делая игру более напряженной.

Простой и интуитивно понятный интерфейс: В 1win lucky jet дизайн игры продуман так, чтобы даже начинающие могли легко вникнуть в условиях и начать играть. Внешний вид и пункт управления максимально просты, что позволяет сосредоточиться на планировании и развлечении от игры.

Высокие коэффициенты и возможность больших выигрышей: Игра Lucky Jet предлагает игрокам шанс на крупные выигрыши благодаря большим коэффициентам. Игроки могут выбирать разные показатели, что позволяет выиграть большую деньги в случае выгодного выбора периода для отобрания ставки.

Динамичное и живое действие: В Lucky Jet игроки могут контролировать за тем, как самолёт поднимается, что добавляет элемент возбуждения. Каждый период непредсказуем, и напряжение от интриги делает игру ещё более захватывающей.

Мгновенные выплаты и безопасность: Платформа 1Win обеспечивает эффективные и безопасные выплаты, что позволяет игрокам принять свои деньги без длительных ожиданий. Также предоставляется в любое время поддержка, что делает процесс игры приятным и удобным.

1Win Lucky Jet официальный сайт https://32.farcaleniom.com/index/d2?diff=0&source=og&campaign=8220&content=&clickid=w7n7kkvqfyfppmh5&aurl=https%3A%2F%2Fusd116.org%2Fwp-content%2Flucky-jet-krash-igra-v-1win-kazino-na-oficialnom-sajte-igrovoj-process-i-vyigryshnye-strategii%2F&utm_source=ogdd&utm_campaign=26607&utm_content=&utm_clickid=g00w000go8sgcg0k&post_type=product&member%5Bsite%5D=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sickseo.co.uk%2F&member%5Bsignature%5D=SEO+firms+appreciate+informed+clients+-+to+a+establish+limit.+Read+the+articles.+Pick+up+an+SEO+book.+Keep+up+with+the+news.+Do+not+hire+an+SEO+expert+and+then+tell+them+you%27re+an+SEO+fellow.+For+example%2C+you+may+be+excited+to+learning+about+all+from+the+SEO+devices+that+could+be+at+your+disposal.+Don%27t+blame+the+SEO+firm+for+failing+to+use+them+at+soon+after.+Measured%2C+gradual+changes+are+best.%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cimg+src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fstatic.turbosquid.com%2FPreview%2F2014%2F07%2F11__08_54_51%2F01whiteboardturbosquidq.jpg1670159b-9d34-458a-aaad-c0686b53bde6Large.jpg%22+width%3D%22450%22+style%3D%22max-width%3A450px%3Bmax-width%3A400px%3Bfloat%3Aright%3Bpadding%3A10px+0px+10px+10px%3Bborder%3A0px%3B%22%3ENother+firm+came+to+us+after+their+previous+seo+got+them+banned+from+A+search+engine.+Coming+to+us+we+couldn%27t+guarantee+any+further+than+advertising+and++%3Ca+href%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Fwww.xn--119-cn7l257m.com%2Fbbs%2Fboard.php%3Fbo_table%3Dcomplaint%26wr_id%3D3801%22+rel%3D%22dofollow%22%3ESICK+SEO%3C%2Fa%3E+marketing+fix+their+website+to+let+compliant+with+search+engine+guidelines+and+work+aggressively+to+these+back+in+the+index.+After+fixing+the+spam+issues%2C+and+almost+a+year+wait.+and+several+phone+calls+asking+%22when%22%2C++seo+services+london+Google+finally+re-included+them%2C+and+with+great+rankings+on+top+of+it.%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+Yes%2C+certain+happened.+Fortunately%2C+keyword+modifications+were+made+and+locations+rebounded+typic&pushMode=popup предоставляет высококачественные условия для игры в lucky jet. Платформа известна своей достоверностью, серьёзностью и высококачественным обслуживанием пользователей. Игроки могут наслаждаться процессом игры, зная, что их ресурсы защищены, а транзакции проходят эффективно. Кроме того, 1Win предлагает премии и промоции для начинающих игроков и постоянных игроков, что добавляет дополнительную ценность и делает игру ещё более интересной.

Lucky Jet — это автомат, которая предлагает необычный игровой впечатление с элементами подхода и вероятности. 1win lucky jet объединяет понятность и разнообразие, предоставляя игрокам шанс испытать свои стратегии и удачу. Если вы хотите волнительное и живое азартное игру, lucky jet станет идеальным выбором. Попробуйте свои силы и насладитесь захватывающим развлечением игры на платформе 1Win!

Pin Up: A escolha certa para amantes de jogos de azar

Quando se trata de cassinos online populares, o Pin Up ocupa uma posicao de lideranca no mercado global de jogos de azar, conquistando milhoes de jogadores em todo o mundo. Este site de apostas se tornou uma referencia por sua interface amigavel, variedade impressionante de jogos, e bonus generosos. Em particular, a versao Pin Up se tornou extremamente popular entre os jogadores cazaques, destacando-se como uma das opcoes mais procuradas na regiao.

Pin Up Casino: Diversas opcoes para jogadores

O pin up casino oferece uma ampla variedade de jogos para seus usuarios, garantindo que todos, desde novatos ate jogadores experientes, encontrem algo de seu agrado. A plataforma inclui caca-niqueis tradicionais que evocam a nostalgia dos antigos cassinos fisicos, alem de jogos de mesa, como blackjack, poker, e roleta, que trazem a experiencia autentica dos cassinos para a ponta dos seus dedos. Alem disso, os caca-niqueis modernos, com graficos vibrantes e temas variados, oferecem uma experiencia de jogo cativante que envolve ate os jogadores mais exigentes.

Os ofertas especiais do Pin Up sao outro diferencial significativo para jogadores novos e veteranos. O bonus de boas-vindas e incrivelmente vantajoso, proporcionando aos jogadores um otimo comeco para explorar a plataforma. Alem disso, o Pin Up oferece devolucoes em dinheiro, promocoes sazonais, e competicoes semanais que garantem que sempre haja algo novo e interessante para os usuarios.

Como comecar a jogar no Pin Up Cassino online

Iniciar sua aventura no Pin Up cassino online e simples e direto. O processo de registro e intuitivo, levando apenas alguns minutos para ser concluido. Uma vez registrado, voce tera acesso total a enorme variedade de jogos, aproveitar dos bonus exclusivos, e participar das promocoes e eventos que mantem a plataforma dinamica e excitante para todos os jogadores.

Nosso site: https://67.cholteth.com/index/d1?diff=0&utm_source=ogdd&utm_campaign=26607&utm_content=&utm_clickid=n28gsokgks44gowo&aurl=http%3A%2F%2Fjiriecaribbean.com%2Fdoc%2Fpinup-cassino-o-melhor-cassino-online-em-brasil%2F&source=og&campaign=4397&content=&clickid=hrx9nw9psafm4g9v&title=joellemonetcream99964&url=https%3A%2F%2Fjoellemonet.com%2F&email=jettmcguigan%40web.de++skin+color+as+this+will+help+to+your+skin+to+become+richer+&smoother__For_greasy_skin_around_the_globe_beneficial%2C_since_it_is_soaks_oil_for_till_10_hours__Give_a_gentle_massage_with_the_face_using_moisturizer_and_apply_it_on_your_neck%2C_to_see_the_perfect_image_%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0AWell%2C_even_if_essential_oils_and_wrinkles_are_strongly_connected%2C_that_doesn%27t_mean_that_all_oils_work_the_same_and_how_the_result_always_be_what_you_expect__There_are_major_differences_between_oil_types_and_you_will_know_exactly_what_you_need_it_if_you_must_cure_your_wrinkles_%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%3Cbr%3E%0D%0A%0D%0Ahealthline_com_-_https%3A%2F%2Fwww_healthline_com%2Fhealth%2Fhow-to-get-rid-of-frown-lines_For_fantastic_cutting_back_on_the_degree_of_food_consume_at_one_setting_will_help%2C_just_be_sure_to_switch_to_five_small_meals_each_working__For_many_men_and_women%2C_they_you_should_be_affected_by_acid_reflux_when_they_eat_a_lot_food__You_can_to_still_end_up_eating_the_very_same_amount_of_food_to_perform_just_divide_it_up_throughout_the_day%2C_instead_of_eating_everything_in_2_or_3_meals_%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A_form-data%3B_name=%22field_pays%5Bvalue%5D%22%0D%0A%0D%0ABahrain%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A+form-data%3B+name%3D%22changed%22%0D%0A%0D%0A%0D%0A—————————1692248488%0D%0AContent-Disposition%3A+form-data%3B+name%3D%22form_build_id%22%0D%0A%0D%0Aform-c673d3ab9883a7e4fa1cec1fd322&pushMode=popup

Alem disso, o Pin Up oferece uma serie de opcoes de pagamento que facilitam a realizacao de transacoes e saques, com suporte ao cliente disponivel 24 horas para ajudar com qualquer duvida ou problema que possa surgir.

Jogos moveis Pin Up: Seu cassino em qualquer lugar

Uma das vantagens mais importantes do Pin Up e a presenca em dispositivos moveis, que assegura que os jogadores possam acessar aos seus jogos favoritos em qualquer lugar, em qualquer situacao. O aplicativo movel do Pin Up esta acessivel em todas as principais plataformas, como Android e iOS, e e totalmente compativel para dispositivos moveis. Isso significa que voce pode desfrutar de seus jogos enquanto esta em movimento, relaxa em casa, ou simplesmente deseja em um ambiente mais confortavel.

Com o Pin Up app, voce nunca ficara para tras nos seus jogos preferidos, pois a plataforma oferece atualizacoes constantes e notificacoes em tempo real sobre novos jogos, promocoes, e eventos, para que voce esteja sempre bem informado das ultimas novidades do mundo dos cassinos online.

Consideracoes finais

O Pin Up casino e indiscutivelmente uma das melhores escolhas para quem busca qualidade em jogos de azar. Com uma interface intuitiva, uma vasta colecao de jogos, e ofertas generosas, o Pin Up proporciona uma experiencia de jogo que atende as expectativas de jogadores novos e experientes.

Se voce esta procurando um site de apostas seguro, que prioriza a experiencia do jogador, o Pin Up e a escolha ideal para qualquer entusiasta de apostas. Experimente o Pin Up hoje e descubra porque ele e considerado um dos melhores entre apostadores em todo o planeta.

Descobrindo o Fortune Tiger: A Aventura do Jogo de Sorte em Sua Tela

Se voce compartilha do mesmo gosto que eu, um devoto pelo mundo dos jogos de azar, sabe que achar a melhor opcao de jogo pode fazer toda a diferenca. Hoje quero falar sobre uma das mais empolgantes vivencias que conheci ultimamente: o demo fortune tiger . Esse slot machine e uma perola rara para quem deseja empolgacao, entusiasmo e, certamente, otimas oportunidades de ganhar.

Sorte do Tigre: Uma Visao Geral ao Jogo

O Fortuna do Tigre e um jogo de slot que mescla graficos chamativos com uma jogabilidade envolvente. Foi criado com inspiracao no energia e na graca do tigre, um ser mistico que encarna felicidade e abundancia em varias culturas. Cada giro e uma possibilidade de trazer a sorte para perto, com a possibilidade de fazer crescer seus rendimentos a cada jogada.

Descubra o Demo do Sorte do Tigre

Se ainda nao se sente a vontade para fazer apostas com dinheiro de verdade, a melhor opcao e experimentar o Sorte do Tigre demo. Essa versao gratis da a chance de sentir todas as funcoes e aprenda as taticas certas sem investir. Eu aconselho com certeza que todos os novos jogadores testem o Tigre da Fortuna demo gratis antes de seguir para as jogadas valendo dinheiro.

Tigre Afortunado: O Poder do Guerreiro nos Jogos de Cassino

O que torna especial Tiger Fortune tao especial? Alem dos graficos impressionantes e dos efeitos de som emocionantes, o jogo fornece muitas linhas de pagamento e uma variedade de bonus que mantem a acao constante. A cada jogada, voce passa por a emocao expandir, especialmente quando os simbolos unicos se juntam na linha, proporcionando grandes conquistas.

Sorte do Tigre 777: O Numero da Sorte

O numero 777 e icone da sorte no mundo dos cassinos, e no Fortuna do Tigre 777, a forca dos tres setes se amplifica. A sequencia certa pode abrir enormes premios, e e justamente essa adrenalina que nos motiva a seguir jogando. Parece que o jogo adivinha quando precisamos de uma grande recompensa e nos desse essa oportunidade.

Nosso site: https://39.farcaleniom.com/index/d2?diff=0&source=og&campaign=8220&content=&clickid=w7n7kkvqfyfppmh5&aurl=https%3A%2F%2Frauldoria.pt%2Fblog%2Ffortune-tiger-jogo-de-cassino-experimente-a-sorte-no-mundo-dos-jogos-de-cassino-online%2F&utm_source=ogdd&utm_campaign=26607&utm_content=&utm_clickid=g00w000go8sgcg0k&post_type=product&member%5Bsite%5D=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sickseo.co.uk%2F&member%5Bsignature%5D=SEO+firms+appreciate+informed+clients+-+to+a+establish+limit.+Read+the+articles.+Pick+up+an+SEO+book.+Keep+up+with+the+news.+Do+not+hire+an+SEO+expert+and+then+tell+them+you%27re+an+SEO+fellow.+For+example%2C+you+may+be+excited+to+learning+about+all+from+the+SEO+devices+that+could+be+at+your+disposal.+Don%27t+blame+the+SEO+firm+for+failing+to+use+them+at+soon+after.+Measured%2C+gradual+changes+are+best.%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cimg+src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fstatic.turbosquid.com%2FPreview%2F2014%2F07%2F11__08_54_51%2F01whiteboardturbosquidq.jpg1670159b-9d34-458a-aaad-c0686b53bde6Large.jpg%22+width%3D%22450%22+style%3D%22max-width%3A450px%3Bmax-width%3A400px%3Bfloat%3Aright%3Bpadding%3A10px+0px+10px+10px%3Bborder%3A0px%3B%22%3ENother+firm+came+to+us+after+their+previous+seo+got+them+banned+from+A+search+engine.+Coming+to+us+we+couldn%27t+guarantee+any+further+than+advertising+and++%3Ca+href%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Fwww.xn--119-cn7l257m.com%2Fbbs%2Fboard.php%3Fbo_table%3Dcomplaint%26wr_id%3D3801%22+rel%3D%22dofollow%22%3ESICK+SEO%3C%2Fa%3E+marketing+fix+their+website+to+let+compliant+with+search+engine+guidelines+and+work+aggressively+to+these+back+in+the+index.+After+fixing+the+spam+issues%2C+and+almost+a+year+wait.+and+several+phone+calls+asking+%22when%22%2C++seo+services+london+Google+finally+re-included+them%2C+and+with+great+rankings+on+top+of+it.%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%3Cp%3E%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E+Yes%2C+certain+happened.+Fortunately%2C+keyword+modifications+were+made+and+locations+rebounded+typic&pushMode=popup

Aposta na Sorte do Tigre: Arriscando na Sua Bencao

Quando chegar o momento certo para realizar sua primeira jogada, o Aposta na Fortuna do Tigre entrega opcoes variadas de valores. O que quer dizer que voce pode comecar com apostas pequenas para conhecer melhor ou arriscar alto com jogadas maiores, se acreditar que a sorte esta a seu favor. Seja qual for o valor da aposta, a experiencia e empolgante.

Resumo: Compensa Jogar o Fortune Tiger?

Com certeza, o Tigre da Sorte e um dos slots mais emocionantes disponiveis no momento. Ele oferece uma fusao exata de entretenimento e capacidade de ganho, tudo apresentado em um ambiente imersivo e visualmente deslumbrante. Entao, se ainda nao testou, va em frente e perceba a razao que Tigre Afortunado atrai tantos apostadores.

Thimble Casino : Plongee dans un Univers de Jeu Exceptionnel

Bienvenue dans le monde fascinant de Thimbles, un etablissement de jeu en ligne ou le divertissement et l’excitation se rencontrent pour creer une experience inoubliable. Que vous soyez un joueur chevronne ou un novice enthousiaste, Thimbles offre un eventail impressionnant de jeux et de fonctionnalites concues pour captiver et satisfaire toutes vos attentes.

Une Plateforme de Jeu Moderne et Innovante

Thimble Casino se distingue par son approche moderne et elegante du jeu en ligne. Des votre arrivee sur le site, vous serez accueilli par une design raffinee qui combine design et fonctionnalite. Le interface facilite la navigation et vous permet de vous concentrer pleinement sur l’experience de jeu.

Le site de thumbles casino est optimise pour offrir une experience fluide et sans interruption, que vous jouiez sur un PC, une iPad ou un telephone mobile. La plateforme est compatible avec tous les principaux navigateurs et systemes d’exploitation, garantissant un acces facile et pratique a vos jeux preferes, peu importe ou vous vous trouvez.

Une Gamme Variee de Jeux pour Tous les Gouts

Au c?ur de Thumbles Casino, vous decouvrirez une vaste collection de jeux, chacun offrant une experience unique et passionnante. Le jeu de gobelets, egalement connu sous le nom de Thimbles game, est l’un des jeux phares du casino. Ce jeu captivant met a l’epreuve votre concentration et votre capacite a suivre le mouvement des jetons sous les gobelets. Avec des regles simples mais un gameplay addictif, le jeu de thimbles est un choix populaire parmi les joueurs a la recherche de defis stimulants.

En plus du Thimbles game, Thumbles Casino propose une large selection de jeux de slots, allant des classiques a trois rouleaux aux machines a sous video sophistiquees avec des images 3D impressionnants. Les jeux de slots sont dotees de diverses fonctionnalites bonus, telles que des spins gratuits, des multiplicateurs de gains et des jackpots progressifs, offrant de multiples opportunites de gagner gros.

Les amateurs de jeux de table ne seront pas en reste avec une gamme complete de jeux tels que le jeu de cartes, la jeu de roulette , le baccarat et le poker. Chaque jeu est concu pour offrir une experience immersive et immersive, avec des regles claires et des graphismes. Les tables sont animees par des croupiers professionnels, creant une atmosphere de casino realiste qui vous transporte directement au c?ur de l’action.

Thimble Casino : Une Experience Personnalisee et Exclusive

Pour ceux qui recherchent une experience de jeu plus personnalisee, Thumbles Casino offre des fonctionnalites exclusives et des promotions attractives. Le casino propose une variete de bonus, de offres regulieres et de programmes de fidelite concus pour recompenser les joueurs fideles et offrir des avantages supplementaires.

Site officiel: https://www.degometal.com/cms.html?pName=sur-mesure&redirect=/cms.html?pID=3¶ms=cE5hbWU9c3VyLW1lc3VyZSZhY3Rpb249c2VuZEZvcm0mZm9ybWJJRD02OTImZXBhaXNzZXVyX0E9JmVwYWlzc2V1cl9CPSZlcGFpc3NldXJfdG90YWw9Jm1hdGllcmVfQT1Sb2JlcnRrZXAmbWF0aWVyZV9CPVJvYmVydGtlcCZwZXJjYWdlX0E9JnBlcmNhZ2VfQj0mbWVzc2FnZT08YSBocmVmPWh0dHBzOi8vamF2aXBlcmV6Y20uY29tL2Jsb2dsaXN0L2Nhc2lub3MtZW4tbGlnbmUtZGVjb3V2cmV6LXRoaW1ibGVzLWV0LXNlcy1tYWNoaW5lcy1hLXNvdXMtcGFzc2lvbm5hbnRlcy8+PGltZyBzcmM9XCJodHRwczovL2phdmlwZXJlemNtLmNvbS9ibG9nbGlzdC9jYXNpbm9zLWVuLWxpZ25lLWRlY291dnJlei10aGltYmxlcy1ldC1zZXMtbWFjaGluZXMtYS1zb3VzLXBhc3Npb25uYW50ZXMvXCI+PC9hPiBcclxuIFxyXG7QsNC70YLQsNC50YHQutC40LUg0YDRg9C90Ysg0LfQvdCw0YfQtdC90LjQtVxyXG7RhNC+0YDRg9C8INGA0YPQvdGLXHJcbm1hbm5heiDRgNGD0L3QsCDQt9C90LDRh9C10L3QuNC1XHJcbtC50LXRgNCwINC30L3QsNGH0LXQvdC40LUg0YDRg9C90Ytcclxu0YHQsNC80LjRgNCwINGA0YPQvdGLXHJcbiBcclxuaHR0cHM6Ly9qYXZpcGVyZXpjbS5jb20vYmxvZ2xpc3QvY2FzaW5vcy1lbi1saWduZS1kZWNvdXZyZXotdGhpbWJsZXMtZXQtc2VzLW1hY2hpbmVzLWEtc291cy1wYXNzaW9ubmFudGVzL1xyXG5odHRwczovL2phdmlwZXJlemNtLmNvbS9ibG9nbGlzdC9jYXNpbm9zLWVuLWxpZ25lLWRlY291dnJlei10aGltYmxlcy1ldC1zZXMtbWFjaGluZXMtYS1zb3VzLXBhc3Npb25uYW50ZXMvXHJcbmh0dHBzOi8vamF2aXBlcmV6Y20uY29tL2Jsb2dsaXN0L2Nhc2lub3MtZW4tbGlnbmUtZGVjb3V2cmV6LXRoaW1ibGVzLWV0LXNlcy1tYWNoaW5lcy1hLXNvdXMtcGFzc2lvbm5hbnRlcy9cclxuIFxyXG7QutCw0YDQvNCwINGA0YPQvdGLXHJcbtGE0YDQvtGB0YLQvNC+0YDQvSDRgNGD0L3RiyDQt9C90LDRh9C10L3QuNC1XHJcbtGB0L7Qu9GMINGA0YPQvdCwINC30L3QsNGH0LXQvdC40LVcclxu0YHQuNC90LTQttC10LQg0YDRg9C90Ytcclxu0LfQvdCw0YfQtdC90LjQtSDRgNGD0L3RiyB5clxyXG4gXHJcbjxhIGhyZWY9aHR0cHM6Ly9qYXZpcGVyZXpjbS5jb20vYmxvZ2xpc3QvY2FzaW5vcy1lbi1saWduZS1kZWNvdXZyZXotdGhpbWJsZXMtZXQtc2VzLW1hY2hpbmVzLWEtc291cy1wYXNzaW9ubmFudGVzLyA+0LfQvdCw0YfQtdC90LjRjyDQt9C90LDQutC+0LIg0YDRg9C90YsgPC9hPiBcclxuPGEgaHJlZj1odHRwczovL2phdmlwZXJlemNtLmNvbS9ibG9nbGlzdC9jYXNpbm9zLWVuLWxpZ25lLWRlY291dnJlei10aGltYmxlcy1ldC1zZXMtbWFjaGluZXMtYS1zb3VzLXBhc3Npb25uYW50ZXMvID7RgdC40L7QvSDRgNGD0L3RiyA8L2E+IFxyXG48YSBocmVmPWh0dHBzOi8vamF2aXBlcmV6Y20uY29tL2Jsb2dsaXN0L2Nhc2lub3MtZW4tbGlnbmUtZGVjb3V2cmV6LXRoaW1ibGVzLWV0LXNlcy1tYWNoaW5lcy1hLXNvdXMtcGFzc2lvbm5hbnRlcy8gPtGA0YPQvdGLINA/0LIgPC9hPiBcclxuIFxyXG7RgNGD0L3RiyDRgtGA0LXQsdCwINC30L3QsNGH0LXQvdC40LXQu9C+0YHRgtGE0LjQu9GM0Lwg0YDRg9C90LfQvdCw0YfQtdC90LjQtSDRgNGD0L0g0YTRg9GC0LDRgNC60LDQv9C10YDRgiDRgNGD0L3RiyDQt9C90LDRh9C10L3QuNC10LfQvdCw0YfQtdC90LjQtSDRgNGD0L3RiyDRgtC10LnQstCw0LcgXHJcbtGA0YPQvdGLINGB0LDQvNC40YDQsFxyXG7QvdCw0LzQuCDRgNGD0L3Ri1xyXG7RgNGD0L3QsCAyMiDQt9C90LDRh9C10L3QuNC1XHJcbtGA0YPQvdCwINC60L7RgdC/0LvQtdC5XHJcbtGA0YPQvdCwINC/0L7RgNCw0LHQvtGC0LDQuSDQt9C90LDRh9C10L3QuNC1XHJcbiBcclxuIFxyXG48YSBocmVmPWh0dHBzOi8vdGhlbmV3c3RpcGEuY

Le programme de fidelite de Thimble Casino est particulierement apprecie, offrant des recompenses sous forme de points bonus que vous pouvez echanger contre des argent de jeu, des bonus ou des cadeaux exclusifs. En tant que membre du programme de loyaute, vous beneficierez egalement d’un acces privilegie a des evenements speciaux et a des tournois de jeu, ajoutant une dimension supplementaire a votre experience de jeu.

Thumbles Casino : Une Plateforme Dynamique et Attrayante